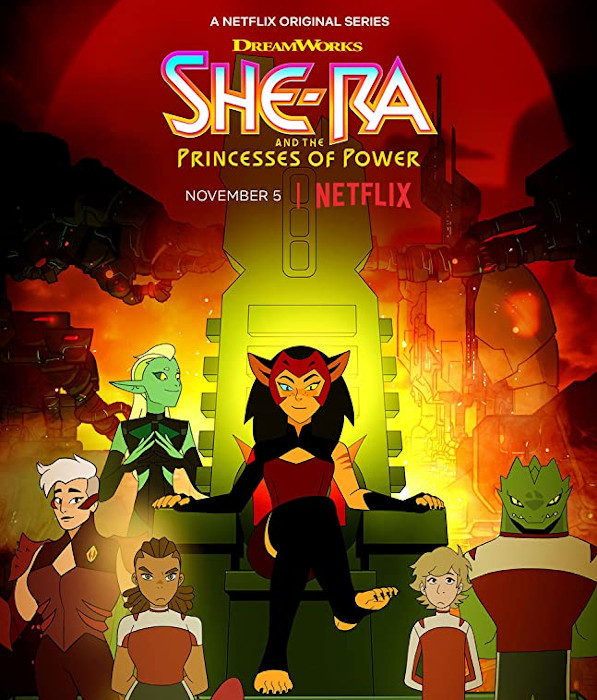

She-Ra and the Princesses of Power (A TV Reflection)

She-Ra and the Princesses of Power isn’t terribly subtle in its moralizing. At one point in S5E12 Princess Entrapta tells Hordak that it’s his differences from his hive-mind brothers that make him special. It also doesn’t need to be. She-Ra is grounded on how well the characters are developed and humanized, from the four-legged non-verbal robot Emily to the Best Friends Squad at the center of the show to the villains. All of the antagonists of the show, from the low-ranking foot soldiers of Lonnie, Rogelio, and Kyle to Hordak, the primary antagonist for the first four seasons, are deeply developed. The development of the antagonists, their internal conflicts and their motivations, help draw me into the show.

I spent a while during season 5 wondering whether Catra would earn her redemption arc. I didn’t think she would. Catra hurt a lot of people over the course of the show. She hurt people as a soldier and as a commander in the Evil Horde, but hurting her enemies as a soldier is easy to understand. It’s less easy to forgive how she treats her friends. Her actions are understandable. She has had too many people leave her and too many people have hurt her too deeply. She is too afraid of people leaving her to let anyone get close, and she pushes everyone who might like her. All of that is understandable, even pitiable. I couldn’t hate Catra. But I also wasn’t sure that I would be able to forgive her. The good things that she did, releasing Adora in S1E9 or freeing Glimmer in S5E3, she did to make herself feel better about how she treated Adora. Catra might have been forced out of working for the Horde, but she refused to apologize for what she did, or make amends, or put work into connecting with the Rebellion. Without any attempt to address who she had been, I didn’t think she would actually grow as a person.

I’m still not sure that I would have forgiven here. But I didn’t grow up with her, like Adora did, and more importantly I’m not as good a person as Adora. Catra didn’t have an easy path to walk for forgiveness. The princesses resented her and neither changing nor apologizing were in her nature. Yet she did both. Catra put in the work to change herself, to move past her anger and her abandonment issues, and become friends with the princesses. What sold me, in the end, was Catra’s apology to Scorpia. She was forced to acknowledge how badly she had treated Scorpia and give Scorpia the opportunity to reject her. That, more than anything that Catra did for Adora, convinced me that she had changed as a person.

The addition of Melog also helped with her characterization. Catra, as much as she put into changing over the course of season 5, still couldn’t express emotions easily or let herself be vulnerable with people. She also didn’t have anyone that she could be vulnerable with - she couldn’t talk about her feelings with Adora, and she wouldn’t talk about them with any over the other princesses. Without Melog, she would have been as isolated among the princesses as she had been with the Horde. Instead, she had a way to express her emotion - Melog licking Perfuma’s face when Perfuma helped her open up or sleeping on Adora’s stomach. Even more important than mirroring Catra’s emotions, Melog gave Catra someone to talk to. She forces Catra to put her emotions into words when she leaves Adora in S5E11. Catra spent four seasons only rarely showing chinks in her emotional armor. Her vulnerability in the final season builds on those rare moments to show a much deeper, more human character.

Although Double Trouble is Catra’s confidant for much of Season 4, they have a very different emotional involvement. Catra has a deep emotional involvement in showing up Adora, which translates to her support for the Horde. Double Trouble has no interest in whether the Rebellion or the Horde win. Their stated motivation is money, but their real interest always seems to be in the performance itself. Double Trouble is a shapeshifter whose principal love always seems to be getting into their roles and deceiving those around them. They change sides when it is convenient for them, deceiving Catra and Hordak with just as much glee as they had previously deceived the Princess Alliance. There’s a certain amount of casual cruelty in that. Catra thought she had finally found a peer in Double Trouble, someone whom she could think of more as her equal than Scorpia. When Double Trouble betrayed her, so soon after Scorpia had left her, Double Trouble hurt Catra very deeply. But Double Trouble always comes off as more amoral than immoral, more interested in playing their roles than in any larger purpose.

That is, ultimately, the most distinctive part of Double Trouble - how deeply their shape-shifting defines who they are. Shape-shifting isn’t just an ability they have, it’s a deeply ingrained part of their character.one of the smaller but more important ways this comes across is in Double Trouble’s gender identity. Double Trouble is nonbinary, as are showrunner Noelle Stevenson and Double Trouble’s voice actor, Jacob Tobia. They have both talked about shapeshifting as a metaphor for their own experiences as non-binary. Stevenson has cited Zam Wessell, the shape-shifting bounty hunter from Star Wars: Attack of the Clones, as being a formative experience for their own gender identity. Tobia has talked more generally about shape-shifting as a common experience for people who are trans or non-binary - “navig ating the world and shaping how we’re putting on ourselves often to survive or to get by.” 1 Perhaps more than any of the other characters in the show, Double Trouble’s abilities aren’t merely something that the character has. They’re a fundamental part of who they are.

The handling of Double Trouble’s gender identity also highlights how well She Ra handles LGTBQ issues. Double Trouble’s gender identity is canonically non-binary. They are always referred to as “they” or “them” - by everyone, from the Princess Alliance to Hordak. Their choice of pronouns is never remarked on, at all. The treatment of the issue is shockingly, wonderfully casual. It’s the treatment given to other LGTBQ topics within the show - Bow’s dad’s relationship, Spinnerella and Netossa, and Catra and Adora, the central relationship in She-Ra. It’s a very hopeful view of a world more perfect than ours.

She-Ra’s characters, especially the villains, are some of its greatest strengths. The show has its own share of flaws. The animation is bright and colorful and the backgrounds are beautiful, but it’s also somewhat flat. Several characters - particularly Swift Wind and Entrapta - are abrasive. The worldbuilding is somewhat shaky. None of those flaws really matter. She-Ra is founded on how well it builds emotional investment in its characters, especially in its villains.